The History of the Black Paths

Man & motor

Craigavon was a response to the increasing urban sprawl and housing shortages in post-war Belfast. The solution was to build a new city and a new industrial centre for Northern Ireland, creating jobs and providing housing for 100,000 people by 1980.Geoffrey Copcutt was appointed to be the new city’s chief architect, before the name of the new city had been decided. Copcutt became increasingly frustrated by Stormont’s interference and local tribal politics, and a year later resigned in a storm of bad publicity.

Though Copcutt was gone, some of his more practical ideas remained baked into the final design. The “linear city” – developed and expanded along a central spine of road and rail networks – was seen as ideal for the area between Portadown and Lurgan, and most notably his solution for separating “man and motor” – adopted from his work in the New Town of Cumbernauld in Scotland.

The biggest single technical consideration is traffic planning. We don’t intend to rely on the application of current American practice – their own systems are already proving absurdly inadequate

Early models for the new city (below) show the transport system as its most defining feature.

On a different level

For this dual network to function, both transport systems were designed to be unimpeded by the other. No footpaths compromising space and speed for cars or posing a potential risk for pedestrians. No traffic lights or zebra crossings to slow down motorists. No dangerous cycle lanes painted along side busy roads for cyclists to squeeze into.

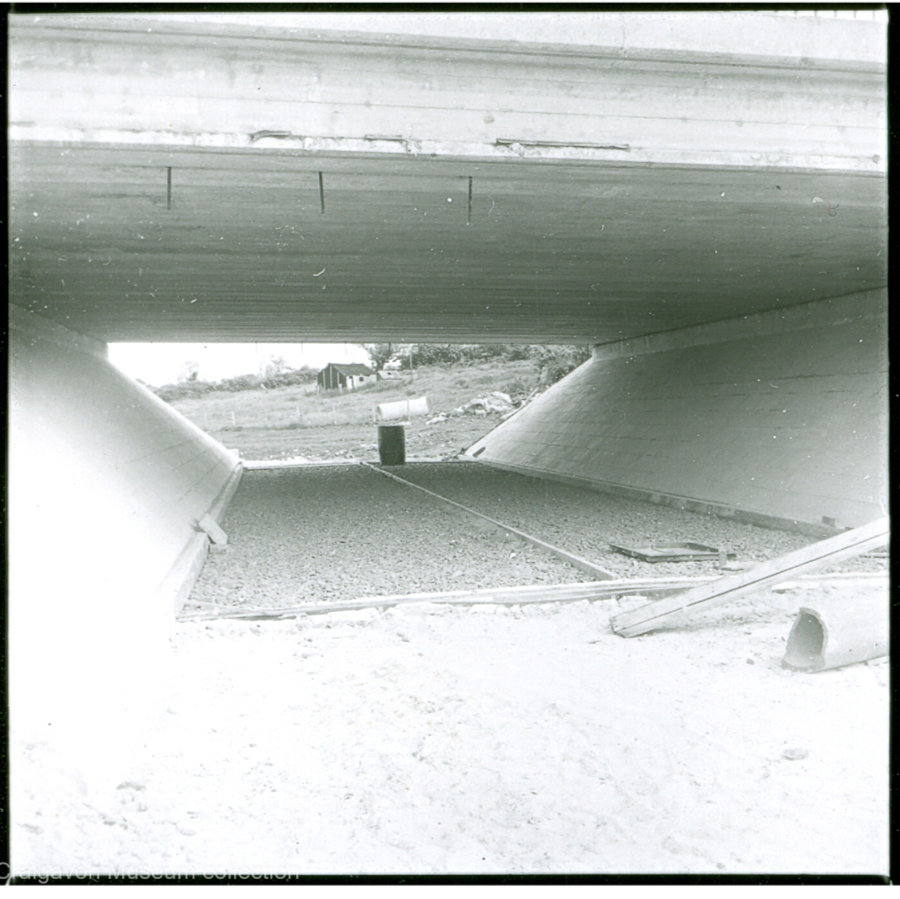

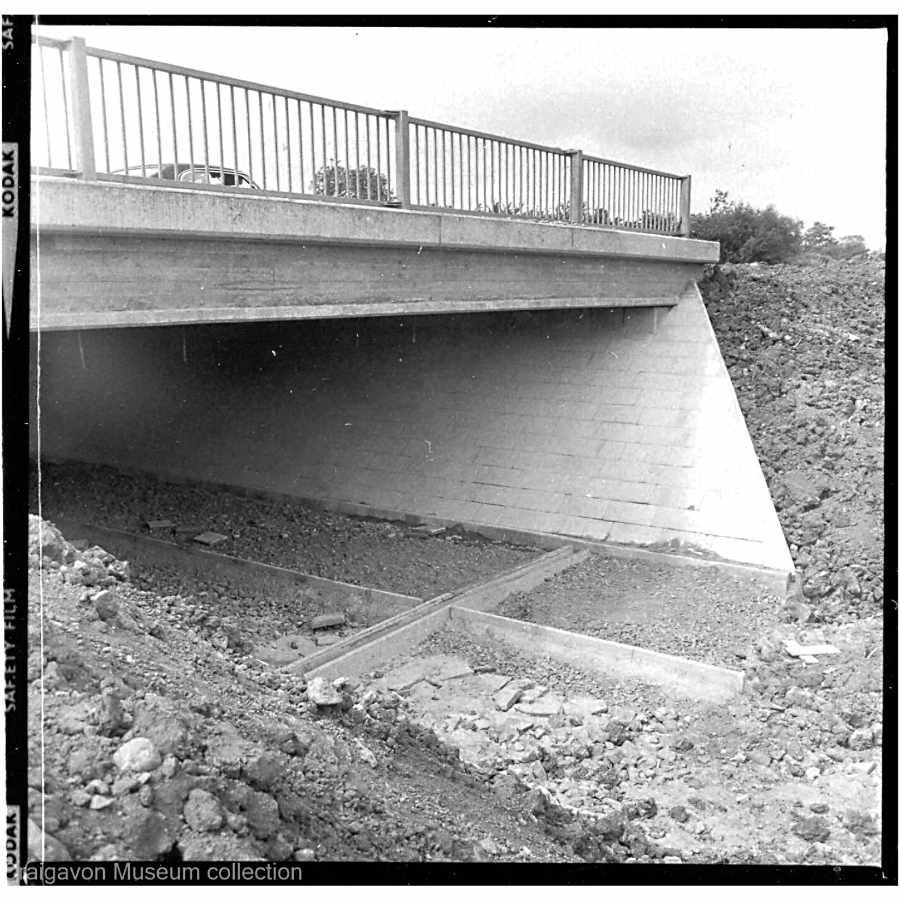

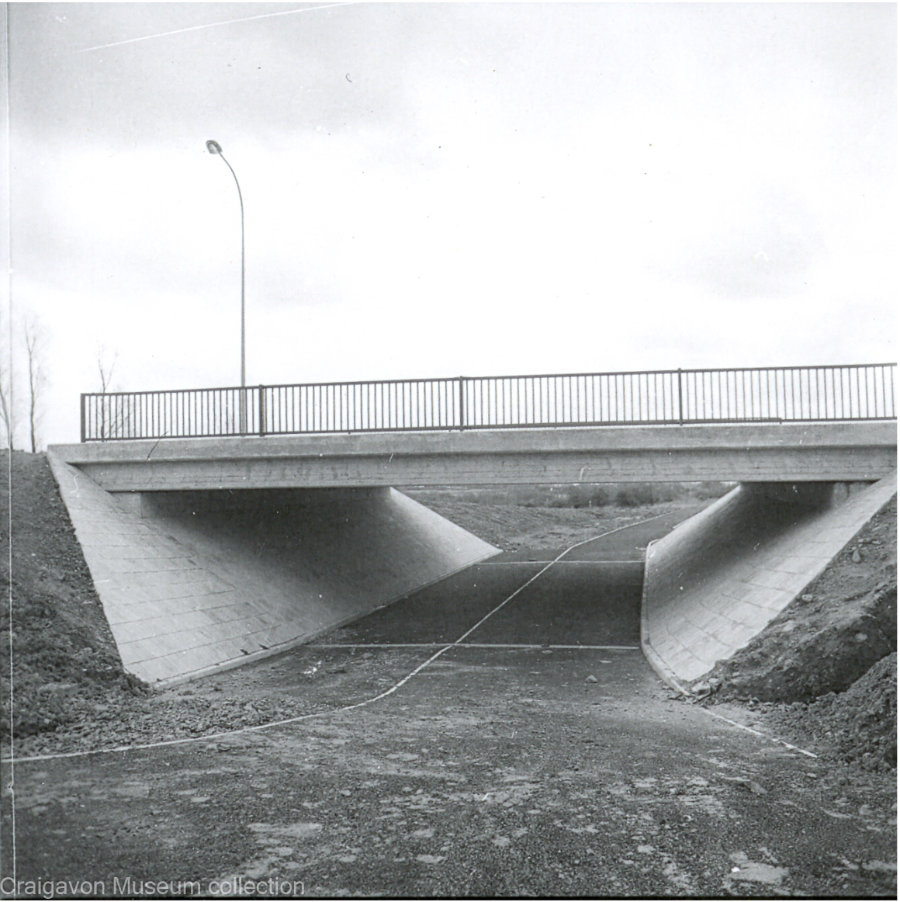

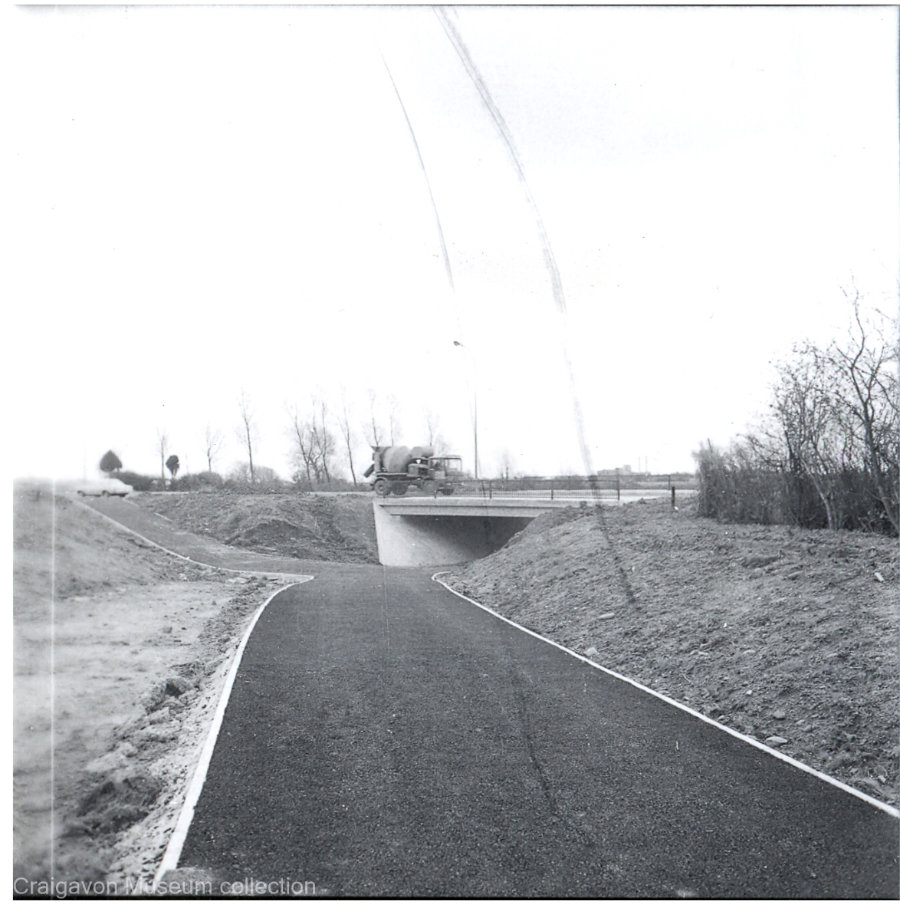

Where the cycle network met the road network, one would pass over or under the other (grade separation). Over 40 of these underpasses were constructed as some of the earliest pieces of built infrastructure in Craigavon (see images below). Many (easily identified by their blue railings) at the edges of Brownlow and Mandeville remain abandoned, overgrown, filled in and waiting for the population growth that stalled during 70s and 80s. Others were unimaginatively overlooked, and failed to be integrated into new housing developments in the 90s and 00s.

(Documented on this Google map)

Incompatible forces

With the underpasses constructed the road network was then completed. Images of the roundabout at Silverwood (below) show this dual system taking shape. Pedestrians and cyclists from Craigavon, would pass under the roundabout at Silverwood, towards Oxford Island and Lough Neagh. Off ramps were added, providing access to the industrial estate at Silverwood, the golf club, and the articifical ski slope.

Man and motor are usually presented as irreconcilable forces - rather than incompatible…. These are not mutually exclusive functions and one does not have to be satisfied at the expense of the other

Black Paths

Black tarmac completed the cycle paths (images below) – giving its users a surface equal to that of the motorists, and the network its nickname. As Copcutt said; “one does not have to be satisfied at the expense of the other”.

Bike bridges

The Black Paths are not only confined to burrowing under the surrounding road network. A series of 6 large bridges carry cyclists and pedestrians high above the dual carriageways towards the central shopping district, and into the city park. Slipways and spiralling stairways descend to bus stops at road level – fully integrating the transport system. These stark, concrete structures (pictured below) have been slowly enveloped over the decades by mature trees and landscaping – helping further separate man and motor.

Going Dutch

We look to the Dutch for inspiration when it comes to active travel. Ironically, Northern Ireland started planning and building Dutch style cycle infrastructure before the Dutch. The key difference is – once the Dutch got started in the early 1970s – they kept going and currently have 35,000km of segregated cycle lanes. Northern Ireland’s experiment was snuffed out in Craigavon and would be doing well to scrape together 100km at present.

The utopian future the designers planned for was unable to cope with the dystopian reality that 1970s & 80s Northern Ireland delivered - where segregation didn’t stop with traffic systems. Craigavon got many things wrong but it got some things right – the Black Paths were undoubtedly one of the things it got right.

Cities are evolving projects taking centuries to establish and develop a sense of themselves. Craigavon – only halfway through its first century – seems to be slowly finding its identity. In 2017, it was seen as the “most desirable place to live” in Northern Ireland. The butt of jokes for decades – Craigavon may yet have the last laugh.

Welcome to the future

The Black Paths are all still there – 50 years on. Away from the Lakes, many of them have been badly neglected with many surfaces looking more green than black. Parts of the network in the Carn Industrial estate have been blocked and are so overgrown that they are in danger of being lost. However, new developments are taking advantage of being located on this unique network. It all lies waiting to be rediscovered, reinvigorated and used as the designers intended. It remains Northern Ireland’s (and Ireland’s) last and best serious attempt to solve the “irreconcilable forces” of man and motor.

If the future of transport is active travel – Craigavon arrived there over 50 years ago.

Images ©Craigavon Museum Collection